Article summary

Humidity control is often sacrificed

Hard-pressed FMs looking to reduce energy bills often turn off humidifiers.

Low humidity increases viral transmission

The body's respiratory immune system needs a mid-range humidity to remain robust and protect health.

Dry air costs in staff sickness

When the indirect consequences of low humidity are seen, humidification becomes an essential element of climate control.

Energy conservation vs humidity control

Jordan Stevens, Sales Manager at Condair, weighs the case for humidification vs the energy it consumes.

Maintaining the optimal level of indoor humidity is essential not only for the success of many manufacturing processes, such as printing, but also for safeguarding human health and well-being. As experts in humidification, we rarely encounter manufacturers turning off their humidifiers to save energy, as the negative impact on production is immediate and significant. In contrast, humidity control is often deprioritized in offices and public buildings in the name of energy savings, despite its critical role in maintaining a healthy indoor environment.

Producing humidification does require energy. For example, it takes about 0.75kW to convert one kg of water into steam. In a typical London office with 250 employees, this could amount to roughly 80,000kg of steam per year, clearly a substantial energy demand. However, what often goes unnoticed is the long-term cost of not humidifying: the impact on occupants’ health and the resulting consequences for business performance.

Unlike temperature, which we notice immediately when it's too hot or too cold, dry air is less obvious. But its effects, such as increased vulnerability to illness, can be severe.

The hidden cost of dry air

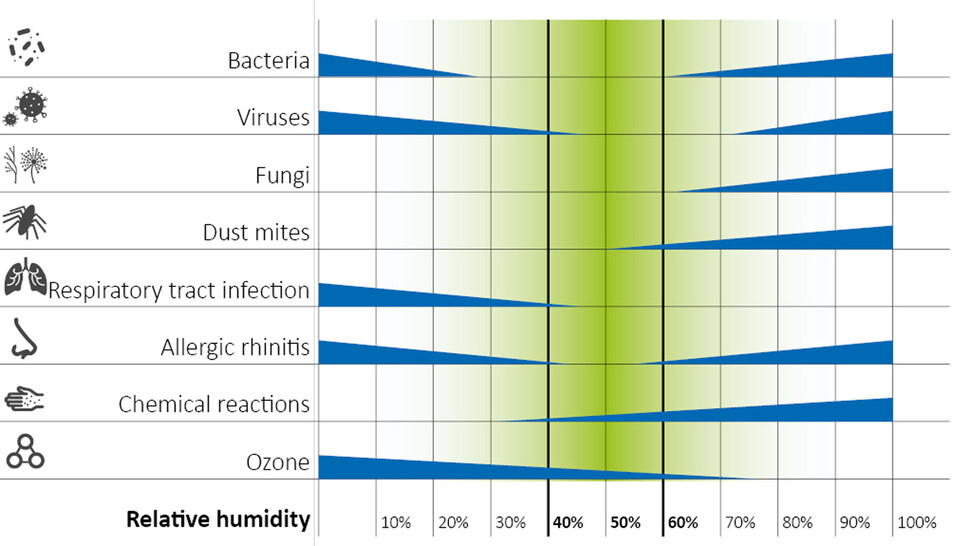

If the link between dry air and increased illness were more visible, the idea of turning off humidifiers to save money would be far less attractive. Back in 1985, Sterling et al. analysed scientific data to understand how humidity affects the survival and spread of health-threatening agents like bacteria, viruses, mould, dust mites, and ozone. Their findings were visualized in what’s known as the "Sterling Chart," which shows that maintaining relative humidity (RH) between 40% and 60% significantly reduces risks to human health. Numerous studies since then have supported this range.

Dry air not only sustains airborne pollutants, but it also directly affects our bodies. It draws moisture from the skin and mucous membranes in the nose and throat, our body’s first line of defence against airborne pathogens. When relative humidity falls below 40%, our immune defences are compromised, making us more susceptible to infections like colds and flu. Over time, prolonged exposure to low humidity can lead to higher illness rates and absenteeism in the workplace.

The business case

According to the Chartered Institute of Personnel and Development’s Health & Wellbeing at Work 2023 report, employees took an average of 7.8 days off due to sickness per year. The leading cause? Minor short-term illnesses like colds and flu. The estimated cost to employers is £500-700 per employee annually. In our typical London office, this could equate to £175k per year. Any business aiming to reduce absenteeism and improve employee well-being should prioritize strategies that limit the spread of these illnesses. Maintaining indoor humidity between 40–60% RH is a proven way to do just that.

So rather than turn off humidifiers to save energy, what can be done to minimise its use? While traditional office humidification systems rely largely on electric steam generators, there can be energy-efficient alternatives. Evaporative and spray humidifiers, which can be integrated into HVAC systems or used as standalone units, require far less direct energy. When used with heat recovery systems to provide the pre-heating needed, these technologies can significantly reduce humidification energy consumption.

Cold water humidifiers can also provide a welcome reduction in cooling costs, when used in the summer to pre-cool incoming fresh air. Evaporative cooling from humidifiers can be used directly on incoming air or, more practically, via an energy recovery system that scavenges cooling from humidified exhaust air prior to external venting.

If replacing the existing steam with adiabatic humidifiers isn’t feasible, there can be other ways to improve energy efficiency. For example, using RO supply water can reduce the need for energy-intensive flush cycles to control mineral build-up in boiling chambers. Regular maintenance and servicing can improve operational efficiency. Optimizing system run times could also be considered if it helps manage energy use without the building dropping below the critical 40%RH threshold.

In the absence of humidification, indoor humidity in a typical UK office can fall below 40%RH from mid-October through to May. This coincides with the height of flu season in the UK. So, if humidity control is sacrificed in the name of energy savings, building occupants are left more vulnerable at precisely the time they most need protection. If the connection between illness, absenteeism and dry air were as visible as the effect of low humidity in printing, few building managers would question the importance of keeping humidification systems running.

Get the free whitepaper "Making Buildings Healthier"

There are many ways in which we can protect ourselves against infectious disease transmission: from good ventilation to maintaining minimum levels of humidity, filtering, lighting and the right choice of materials.

Find out more by downloading your copy of "Making Buildings Healthier". It includes a very useful risk assessment checklist for your own building.

Listen to this 10-minute podcast on how maintaining 40-60% relative humidity indoors is important in combatting the spread of viral infection.

Get in touch with us

Contact us

Contact the UK office by phone, email or webform.

Find your international Condair representative

If you're outside the UK, find your local representative.